- Home

- Wexelblatt, Robert;

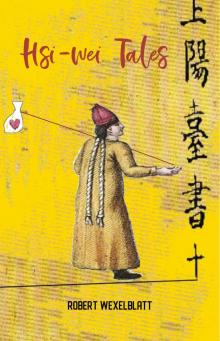

Hsi-wei Tales

Hsi-wei Tales Read online

Contents

Praise for Hsi-wei Tales

Hsi-wei Tales

Copyright © 2020 Robert Wexelblatt. All rights reserved.

Hsi-wei’s Skull

How Hsi-wei Became A Vagabond

Hsi-wei’s Famous Letter

Hsi-wei’s Justice

Hsi-wei’s Grandfather

Hsi-wei and the Tale of the Duke of Shun

The Sadness of Emperor Wen

Hsi-wei and the Hermit

Yellow Moon at Lake Weishan

Hsi-wei and the Good

Hsi-wei Cured

Hsi-wei, the Monk, and the Landlord

Hsi-wei and the Exile

Hsi-wei and The Magistrate

Hsi-wei and Mai Ling’s Good Idea

The Bronze Lantern

Hsi-wei and the Funeral

Hsi-wei’s Letter to Ko Qing-zhao

Hsi-wei’s Visit to Ko Qing-zhao

Hsi-wei and the Witch of Wei Dung

Hsi-wei and the Grand Canal

Hsi-wei and the Rotating Pavilion

Hsi-wei and the Liuqin Player

Hsi-wei and the Twin Disasters

Hsi-wei and the Southern War

Hsi-wei and the Village of Xingyun

Hsi-wei and The Three Threes

Hsi-wei’s Last Poem

Acknowledgments

Praise for Hsi-wei Tales

Hsi-wei Tales is an imaginative, vivid creation that brings historical Sui Dynasty China alive: the rich, the educated, the politically privileged, the working class, and the poorest of the poor, all are tied together by a humble, itinerant shoemaker who is a skilled craftsman and a famous (yet unassuming) poet. He has the wisdom of the careful observer wed to the humility of someone who is unaware of his gifts. He values the shoes he makes more than his poems, but his poems and life have the loveliness one finds in work that is finely crafted. He is a wanderer, a lover of simple things, and has the gift of finding beauty and joy in conversation and interaction with anyone of any class, as long as they commit themselves to embracing the world. The stories are deceptively simple, with depths that repay more than one reading. Characters are finely drawn with delicate brush strokes that one would expect from the best of ancient Chinese artists and calligraphers. Hsi-wei is a welcome guest whose presence is more than ample payment for allowing him to visit.

-Michael L. Newell, poet, whose most recent works are Meditation of an Old Man, Standing on a Bridge, and Traveling without Compass or Map, both from Bellowing Ark Press.

Robert Wexelblatt’s latest wisdom gift is his collection of stories about the peasant/poet Hsi-wei, a survivor of the short-lived Sui Dynasty, a time of wars and outrages in which rulers used their subjects as so many bricks to build a great wall. Still, courage, wit, and beauty make their appearance in Hsi-wei Tales, nourishing a troubled world and helping to preserve some of its more admirable inhabitants. The vagabond poet plays a role in the balancing scales of society as nature balances the seasons of the year. Rogues are outwitted, worthy lives plucked from danger, pretension and falsity revealed. As the ever modest Hsi-wei notes, “at its best, poetry is language made unforgettable.” Both the poetry and the prose in these tales offer gem-like images of nature—“a steady thing,” Hsi-wei tells us, “punctuated by seasons of peace and war, plenty and famine”—and a changeless humanity that are deserving of contemplation and a delight to read.

- Robert Knox, author of the novels Suosso’s Lane and the forthcoming Karpa Talesman.

Dear Hsi-wei, from your ancient land of misted mountains and still lakes where you cross borders and thresholds full of strife, leaving poems and peace in your wake, I welcome you to our time. We need your unassuming wisdom and keen observations, your straw sandals and your quiet dedication to justice. For as you write “apparent stability is really the ceaseless/setting right of countless imbalances.” Welcome, Hsi-wei. Long may your poems be sung!

- Elizabeth Cunningham, author of The Maeve Chronicles, The Wild Mother, etc.

Hsi-wei Tales

Robert Wexelblatt

Regal House Publishing

Copyright © 2020 Robert Wexelblatt. All rights reserved.

Published by

Regal House Publishing, LLC

Raleigh, NC 27612

All rights reserved

ISBN -13 (paperback): 9781947548930

ISBN -13 (epub): 9781947548947

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019941550

All efforts were made to determine the copyright holders and obtain their permissions in any circumstance where copyrighted material was used. The publisher apologizes if any errors were made during this process, or if any omissions occurred. If noted, please contact the publisher and all efforts will be made to incorporate permissions in future editions.

Cover images © by by Svetoslav Tatachev”

Author photograph by Boston University Photo Services

Regal House Publishing, LLC

https://regalhousepublishing.com

The following is a work of fiction created by the author. All names, individuals, characters, places, items, brands, events, etc. were either the product of the author or were used fictitiously. Any name, place, event, person, brand, or item, current or past, is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Regal House Publishing.

Printed in the United States of America

Hsi-wei’s Skull

Chen Hsi-wei was born in the latter half of the sixth century, at the close of the troubled period of the Six Dynasties and at the beginning of Sui rule. His verses, though original, are characteristic of the times, except for his frequent use of vulgar idioms and southern dialects. Recently a curious manuscript of Chen Hsi-wei’s has come to light.

According to a brief preface added by an unknown hand, it was at the request of a certain lady-in-waiting that Chen wrote this account of one of his well-known but perplexing poems, popularly called “My Skull” after the final words of the fourth stanza. Evidently composing this explanation especially inspired Chen Hsi-wei because he supplied something more than was requested, virtually an account of his becoming a poet.

Freely translated, the poem reads as follows:

In Pingyao, as they began to lash my back and chest,

I could just hear little girls chanting “Rice-Bowl-Rice”:

Through green doors, across red pavement, that jolly song.

When they dragged me off to be questioned in Nanyang

Melancholy music wafted from Three River Tavern,

Just the sort to make barge men soften like medlars.

I curled up contentedly by a great sow near Chuchow,

No less warmed than she by our soiled straw,

Our cradle rocked by Feng’s fierce horsemen tramping by.

Wuchow’s streets ran with festive dragons, crackers burst,

Women warbled, children cheered, babies bawled as

General Fu ran his so-eager finger over my skull.

***

Honored Lady, deeply touched by your request, I rush to fulfill it. Please overlook my awkwardness, put it down to my haste to gratify your curiosity.

You must first know that I was born a peasant. My people lived in a village not far from the capital. In fact, you may have at some time enjoyed a banquet supplied from our farm which used to be famous for its ducks.

&

nbsp; There was nothing unusual about my rearing or indeed about me, save for one peculiar capacity which I will mention presently.

In those first days of the new dynasty the Empire was still riven by strife. Warlords threatened the peace on every hand. Ruthless bandits terrorized the countryside. One of the greatest problems with which the new government had to cope was the getting and sending of letters and dispatches. Under the conditions of the period, no postal system could be counted on.

It happened that the Emperor’s ministers needed to get a message through to our southern army. Apparently, nothing less than the survival of the Empire itself depended on the safe delivery of this message; moreover, disaster could be counted on should the information fall into the wrong hands. But to get to the southern army, a messenger must pass through vast lawless lands and many regions under the thumb of one or another warlord.

The Emperor’s ministers knew that an armed force sent south with the message would only call attention to itself and, whatever its strength, was bound to fall prey either to warlords or bandits. Nor could couriers be trusted, for they were only too likely to be captured along with the message. I am told that the stratagem adopted was suggested to the First Minister by an old scholar who had come across it in an obscure history of the Chou dynasty.

A decree was put about the vicinity of the capital that the Emperor required a healthy young man with three qualities: bravery, illiteracy, and fast-growing hair. Rewards were promised to any family that should supply such a man.

You will recall my mentioning that in my youth I possessed only one noteworthy peculiarity. This was that my hair grew so quickly it needed cutting every week. While I cannot claim to have been especially brave, I certainly could neither read nor write.

Peasants are not only illiterate but also poor, My Lady. My parents were poor indeed, and when they heard the decree of the Emperor read out in the marketplace they did not hesitate to bundle me off to the capital. They even gave me a duck for the Emperor’s minister. I carried it on my back.

Of course I was not the only peasant lad to show up in the palace’s outermost courtyard on the appointed morning. There were scores of us. The guards, who instantly relieved me of my duck, made us wash our faces in great vats of water then lined us up in ranks. “Stand straight!” they roared at us and we did so for half an hour until a group of distinguished personages issued from a doorway. I wonder if you, My Lady, can imagine our awe when I tell you that the First Minister personally walked among us and, as we had been forbidden to kowtow, looked directly into our faces. I had never seen anyone like him, so grand and wise, so haughty and disdainful, draped in silks and taking little steps on shoes that elevated him well above even the tallest of us. We trembled before him—beneath him I should say, for the tiled roofs of the palace, the height of its walls, the scornful regard of the First Minister, everything looked down on us and made us feel stuck to the earth like beetles.

Many were dismissed at once. Some looked weak, had coughs or boils. Some were too fat, had bowed legs or thin hair. A few city boys, dressed up by their parents to look like peasants, in terror of the First Minister confessed that they could read. They too were sent packing. About forty of us remained. We were conducted into one of the palace’s stables. The place looked to me vast enough to hold my whole village. Here we knelt six at a time. A small patch on the back of our heads was shaved. Then we were each issued a tiny bowl of rice with a few vegetables and locked into the stable for the night with our guards. Anyone heard groaning with discomfort or complaining about the food was immediately seized and sent away.

Those of us who remained were fetched out at dawn and told to race to some privies several hundred yards away. Note was taken of our speed. Nature’s call being particularly insistent that morning, I ran faster than most. Once we had accomplished what was necessary at the privies, the guards again commanded us to wash in the vats of water, except for our heads that were to be kept dry. Once again we were arranged in ranks. “On your knees! Bow your heads!” yelled the guards. This time the First Minister did not participate. Instead, we were examined by clerks who held rods to the shorn spots on our heads. Each clerk had a scribe behind him to record our names and the results of the night’s growth.

An hour later, two guards escorted me trembling with fright into the palace itself. I walked through magnificent galleries, down burnished and lacquered corridors into a magnificent room with a high teak desk and many opulently cushioned couches. On one of these couches, raised upon a low dais, reclined the First Minister.

I kowtowed.

“Explain matters to him in plain language,” said the Minister gravely to one of his attendants.

This the attendant did and plainly enough. The crucial message to the army in the south, the communication on which the whole of the Empire depended, was to be entrusted only to me. There would be no scroll to deliver, no words for me to memorize. Scrolls can be taken away, memorized words divulged either in one’s sleep or under torture. No, the message was to be inscribed in indelible ink on my shorn skull. The moment my hair had grown back sufficiently to hide it, I should depart for the south. I would travel on foot but as rapidly as possible and as inconspicuously too. I was to be given barely enough money for the journey and should take on the role of a peasant lad forced on the roads after being thrown out by his family. I must expect to be threatened, captured, even tortured along the way. At all costs, though, I must get through and never tell anyone except General Fu himself about the secret message on my head. The general would himself write a message for me to take back.

This, they told me, was the command of the Emperor himself and therefore my mission was divine.

Perhaps you can imagine how dumbfounded I was yet also how proud. It was as if I had been suddenly shown some special merit in myself. Looking back now, I wonder how many of us boys might have listened to that speech, felt the same shocked pride, how many were sent into the cauldron of the warring states, and whether I was just the only one to make it all the way to Wuchow and back. I wonder also about that message I could not read but which I, in a sense, was. I wonder how essential it actually was, and whether it arrived in time. In Wuchow General Fu said nothing to me. I might have been a scroll. He simply directed a scribe to paint a few characters on my freshly shaved skull and kept me under close guard for the few days it took for my hair to grow back.

And so, My Lady, the poem about which you were so gracious as to be curious merely records a few images from my journey. However, the first of my travels introduced me not only to the vastness of the Middle Kingdom and the variety of its peoples, but also to the grandeur of civilization and the cruelty of barbarism. I learned something else as well. I learned the diversity of tongues and what I might call the weight of words.

I returned to the capital as illiterate as when I had departed so many months before but with an inextinguishable burning to become educated. I who had borne language on my empty head yearned to master its secrets. That is why when the Emperor’s clerks offered me gold and land and concubines I begged instead to be taught. This made them howl with laughter. They must have informed the First Minister because he sent for me.

“I am told that all peasants dream of land and money and women. Why do you, a peasant, wish to be educated?”

Though I lay prostrate before him, I replied with an audacity I must have somehow picked up on my journey. “Your Excellency, would you consent to surrender your education, to forget not only all you have read but even how to read, for land you could not describe, wealth you could not count, or a woman with whom you could not intelligently converse?”

The room grew hushed at this unheard-of temerity, but lucky for me the First Minister, notwithstanding his contempt for peasants and despite his haughty smile, replied seriously. “I see your education has already begun, boy. Very well. We shall see that it continues, but there shall be no land or gold or women.

”

There was never, My Lady, a truer prophecy.

I was assigned a stern tutor, the Master Shen Kuo, with whom I spent the next eight years at hard intellectual labor. I seldom saw my parents, though they did me honor for the gifts they received from the Emperor. My first nephew is named Hsi-wei.

In the end I became a poor poet, which is just what I wanted to be. I believe the happiest moment of my life was the first time I overheard “The Yellow Moon at Lake Weishan” sung in a tavern by some students far gone in their cups.

Yet I confess to you here, My Lady, how little has altered since my fate was first decided. A poet too is a sort of messenger from the Emperor; he too must remain faithful to his mission, inured against the hardships of his travels. To this day I still make my way through the wide world in search of General Fu with mysterious characters I myself cannot always understand inscribed upon my skull.

How Hsi-wei Became A Vagabond

Once again Hu Zhi-peng had brought a small gift. This time it was a pomegranate from the south, quite a rarity in the days when Yang Jian had yet to unite the two kingdoms and declare himself Emperor Wen of Sui.

Tian Miao sat up straight, her back not touching the chair. She thanked Hu humbly and sincerely but didn’t know what to do with her hands or, indeed, her life. She prepared herself to receive Hu’s guidance; for he never arrived with presents alone; there was advice as well.

When Tian Miao became a widow at the age of seventeen Hu Zhi-peng had been of great service to her. He helped her secure the small house in which she lived and the one hundred mou of land which he then arranged for her to lease to two peasant families. Hu had also found her a servant, Jingfei, a decent if garrulous peasant widow of forty. Miao was obliged to be grateful to the merchant.

Hsi-wei Tales

Hsi-wei Tales